This article originally appeared in print journal Nov/Dec 1999.

See, it was supposed to go like this. Humanity was going to become ever smarter and more evolved, science and technology were going to give us utopian appliances and toys, and a be-here-now approach to life was going to make pie-in-the-sky totems like religion dwindle away.

Acclaimed Harvard theologian Harvey Cox boldly predicted the demise of religion and the ultimate rise of secularism in his groundbreaking 1965 book, The Secular City. “The rise of urban civilization and the collapse of traditional religion are the two main hallmarks of our era,” he writes in the book’s introduction, in which he prophesies the imminent “loosing of the world from religious and quasi-religious understandings of itself…[and] the breaking of all supernatural myths and sacred symbols.”

But things didn’t turn out that way, and by 1995, Cox was singing a far different tune. In his introduction to Fire from Heaven: The Rise of Pentecostal Spirituality and the Reshaping of Religion in the Twenty-First Century, Cox apologizes for his earlier predictions. “Perhaps I was too young and too impressionable when the scholars made those sobering projections,” he writes. “Today, it is secularity, not spirituality, that may be headed for extinction.”

The Proof’s on the Silver Screen

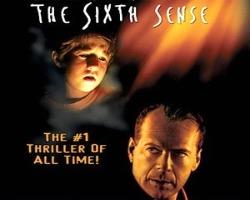

Indeed, spirituality has been omnipresent in pop culture for the last few years—and one of the places it has been most pervasive in 1999 has been at the local Cineplex. And things didn’t end with The Blair Witch Project, profiled here in the previous issue of Youthworker. This September, The Sixth Sense and Stigmata were battling each other for the title of box-office champ.

The Sixth Sense is a moving and sometimes disturbing look at communication with the dead (also the subject of the recent film, Stir of Echoes, in which star Kevin Bacon is hypnotized and begins existing on a hellish spiritual plane).

In The Sixth Sense, star Bruce Willis tries to help Cole, a nine-year-old boy whose troubled world is regularly invaded by the spirits of the deceased. During one emotional moment, the boy tells Willis, “I see dead people,” and by the end of the film, some of those who’d doubted the boy or called him a “freak” begin to believe.

The film is well produced, features a stellar performance by Willis, and ends with a mind-boggling cinematic twist that inspired many viewers to see it more than once. All in all, The Sixth Sense does a more compelling job of portraying spiritism than most Sunday sermons do in articulating more orthodox Christian views on the afterlife.

Stigmata treats spirituality much differently, however. Instead of taking its subject seriously, it unapologetically exploits spiritual themes for Exorcist-type thrills. Patricia Arquette plays Frankie, a woman possessed by demonic spirits after her mother sends her a Christian relic from Brazil.

In addition to its weird, disgusting special effects, one of the biggest problems with the film is its confusion about stigmata, which tradition holds are bleeding marks on the hands, feet, and head (the same places where Jesus bled during his crucifixion) that have allegedly appeared on the bodies of devout Christians such as St. Francis of Assisi down through the ages. But in the film, the marks are demonic in origin and afflict Frankie, an ardent nonbeliever—all of which led critic Roger Ebert to call the film a source of “endless goofiness,” calling it “possibly the funniest movie ever made about Catholicism.”

The latter months of 1999 feature even more spiritually-themed films:

• Lost Souls stars Winona Ryder and Ben Chaplin in a battle against the devil.

• In Holy Smoke, Harvey Keitel plays a cult deprogrammer with a thing for Titanic‘s Kate Winslet, who’s become ensnared in an Eastern sect.

• Bringing Out the Dead. Nicolas Cage is an ambulance paramedic who’s plagued by the ghosts of those he couldn’t save.

• Milla Jovovich stars in Joan of Arc this November (the medieval, teenage saint was also the subject of a CBS-TV miniseries earlier this year.)

• In the apocalyptic End of Days, Arnold Schwarzenegger tries to prevent Satan from mating with an earthly bride (November).

• And in The Third Miracle (December), Ed Harris plays a struggling Catholic priest whose faith is revived by a holy relic, which this movie treats with much more dignity than does Stigmata.

Let’s not forget Dogma—the controversial religious comedy by director Kevin Smith (Chasing Amy and Clerks) which was completed eons ago but has been a cinematic hot potato due to fierce opposition from Catholic and evangelical groups. A parody on the battle between good and evil, Dogma features Ben Affleck and Matt Damon as fallen angels, rocker Alanis Morissette as God, comedian Chris Rock as an angry apostle, Salma Hayek as a heavenly muse, and Linda Fiorentino as the heroine/messiah. George Carlin, Janeane Garofalo, and Jason Lee appear as well.

Director and writer Smith—a self-described, practicing Catholic—had promised the film will find a distributor by November. If so, all you-know-what will break loose at theaters across the country before Thanksgiving. You can check out the film’s official website—www.dogma-movie.com—for more information.

And down at your local video store, you can find Robin Williams playing a loving husband who retrieves his wife from hell in What Dreams may Come, and Keanu Reeves playing a messiah figure in the virtual-reality drama, The Matrix.

What Gives?

According to people who think about the theology of film for a living, we shouldn’t be surprised to see our culture’s beliefs and doubts played out on the big screen.

“Film is probably the most characteristic and influential medium of our current culture,” says theologian Robert Jewett, author of the recently released St. Paul Returns to the Movies (Eerdmans)—a sequel to his 1993 work, St. Paul at the Movies.

John Wood, who teaches a “Christianity and film” course at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, is particularly intrigued by the Star Wars series, which serves up a syncretistic sampling of Christian themes (the battle between good and evil and ultimate redemption), ancient Eastern philosophy (the all-is-one pantheism of the Force), New Agey human potentiality (“Concentrate on the moment,” Jedi Master Qui-Gon Jinn tells Anakin in this year’s prequel installment, The Phantom Menace. “Feel, don’t think. Use your instincts”), and timeless mythological motifs such as the hero, the dream, and the journey of transformation—all of which are aspects of something the late Joseph Campbell called the Western world’s “monomyth.”

“These films are touching on a deeper chord,” says Wood. “Star Wars says that you have the Force, you have the power, and ultimately you can win over evil.

“Perhaps the church today doesn’t communicate redemption and hope to as many people as it once did, and people are grasping for something. As a result, you have all these people spending the night outside the theater waiting for tickets because these films give meaning to their lives, which is kind of scary.”n