Excitedly, the boys scattered the baseball cards across their bedroom floor without regard for the merchandise’s future value on the trading market.

Crease marks? Fuzzy corners? Who cares! This was no time to worry about a mint-condition collection. There were bedroom baseball lineups to be picked, for Pete’s sake!

Speaking of Pete, he was available on the carpet. You could do a lot worse than Pete Rose, baseball’s all-time hit king. But young Adrian Gonzalez always reached for someone else first: Tony Gwynn. As a San Diego area native and a left-hander, Adrian adored Gwynn, another lefty whose .338 lifetime batting average for the hometown Padres punched his ticket into both Cooperstown and Adrian’s heart.

Usually, Will Clark was drafted next. My, oh my, Will the Thrill sure had a sweet stroke. Then, another lefty: Darryl Strawberry. With his pre-pitch bat waggle, exaggerated leg kick, and powerfully loopy swing, the Straw Man was always a favorite.

On and on it went until Adrian and his two older brothers, David Jr. and Edgar, finished their lineups. Each team had to reflect all nine defensive positions. (Stacking the lineup with Mike Schmidt and Wade Boggs—two third baseman—was strictly taboo.)

Out came the plastic bat. Next, the ball—usually a wad of tape or balled-up socks. Finally, the bases…

Uh, let’s see. How about the bed, the closet door, and that pile of dirty clothes? What about home plate? Aw, heck, let’s get started. Just throw something down on the floor.

And batter up!

Once bedroom baseball started, the boys tried to mimic each player’s real-life swing. Every square inch of the room was demarcated for the type of hit it produced. The top of the far wall was a home run. There were plenty of those.

Adrian and Edgar’s battles, in particular, were epic.

“When I got back from school, they were already playing,” recalled David Jr., who is eight years older than Adrian and four years older than Edgar. “Whoever won, they were the champions of the world. When Adrian won, he’d be shouting it all over house. Edgar would get mad and want to play again. Same thing the other way.”

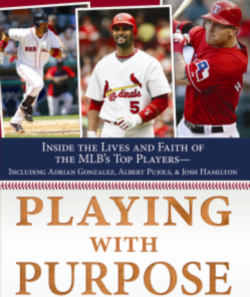

Adrian has come a long way from those halcyon childhood days, bathed as they were in baseball, simplicity, and the SoCal sun. He is now the Boston Red Sox’ newly minted superstar, a $154 million slugger who is quickly etching his name into franchise history with his gorgeous swing. After the magnificent season he fashioned in 2011—a .338 batting average that was second best in the major leagues and 213 hits that tied him with Michael Young of Texas for the most in the majors—Adrian is generally acclaimed as one of this generation’s greatest hitters.

Just don’t expect any of this to faze him. All the hubbub in Hub City elicits little more than a shoulder shrug from this twenty-nine-year-old batsman who’s in the prime of his career. Don’t let his nonchalance fool you, though. Adrian’s levelheaded outlook has as much to do with his deep Christian faith as it does with his mellow personality. He mixes his SportsCenter-highlight abilities with genuine Christlike humility as well as anyone in the game today. For Adrian, the dichotomy fits like a well-oiled mitt.

“I don’t want to be remembered in baseball,” he said. “I want to be remembered as a good witness for Christ.”

At this point, Adrian is destined for both.

All in the Family

Born on May 8, 1982, in San Diego, Adrian always dreamed big. If he wasn’t imitating his favorite baseball hero’s swing, he was imagining himself as a music star. In one classic family photo, he sported a heavily gelled Mohawk while using a tennis racquet like a Jimi Hendrix Stratocaster. (To this day, family members are still puzzled at what the ski gloves and boots were for.)

Alas, musical stardom never panned out for Adrian. But boy, the kid sure rocked it on the diamond.

Adrian’s love for baseball comes from his father, David Sr., who grew up dirt-poor in Ciudad Obregón, a large city in Mexico’s arid Sonoran Desert region, where he sold popsicles and ice cream sandwiches to anyone with a parched tongue and a few pesos. When he grew older and was asked to help support his family, David Sr. dropped out of high school and started working for an air conditioning company. He was always a good handyman.

But he could also play béisbol. He was a big, strong first baseman with huge wrists that required custom-made watches. Maybe that’s what happens when you lug AC units up and down stairs all day long.

While those Popeye forearms produced plenty of pop, he was also stealthily fast on the base paths, enough to earn the nickname El Correcamino—”The Roadrunner.”

David Sr.’s skills are part of Gonzalez family lore. In the days before the San Diego Padres’ inaugural major league season in 1969, as the story goes, a Padres scout saw the Gonzalez clan playing baseball during a family reunion in the San Diego area and set up a scrimmage. After Team Gonzalez beat the pro squad, the Padres extended tryout offers to David Sr. and his cousin, Robert Guerra. David Sr. declined for financial reasons, but his passion for the game never waned.

He played for the Mexican national team in the late 1960s and early ‘70s and attracted other professional offers. But by then, his business was making more money than Mexican baseball paid.

The family immigrated to Chula Vista, a San Diego suburb a few miles north of the border, prior to Adrian’s birth and moved to Tijuana when Adrian was a year old. But the air conditioning business was doing so well that the Gonzalezes could afford to keep a home in both cities. Oftentimes, the family would spend their weekends in Tijuana—Adrian played in elite leagues in Mexico growing up—but would return to their Chula Vista home on Sunday nights since the boys had school in the morning. The consistent border crossings aided Adrian’s baseball and bilingual abilities.

As each son came along, David Sr. baptized him into baseball. From his earliest memory, Adrian recalls throwing a tennis ball against the side of his house, glove in hand, eagerly awaiting his older brothers’ return from school to play with him.

David Sr. would often take his sons to a nearby field for infield practice—David Jr. at shortstop, Edgar at second, and Adrian at first. Even as an ankle-biter, Adrian wouldn’t stand for any patronizing lobs.

“I can catch it!” he’d squeal in protest.

“No you can’t,” his brothers retorted, laughing.

But sure enough, little Adrian showed a preternatural ability to catch bullets and dig out bouncers.

“He always wanted to be a part of us,” David Jr. recalled. “He was always above his age group. We didn’t baby him.”

As David Sr.’s business took off, he was able to provide his sons with opportunities that he never had growing up. He built an enormous backyard batting cage at their Chula Vista home. That was really cool until one day…crash! The boys had used the cage so much that a hole had formed in the protective netting.

The poor window in the neighbor’s house never saw it coming.

For the good of all houses within range, the brothers took up Wiffle ball. But this wasn’t just any ol’ casual game. When it came to competition, the Gonzalez brothers didn’t do casual. This was no-holds-barred Wiffle.

At first, Edgar seemed to have the upper hand. So Adrian bought a book on how to throw Wiffle pitches—yes, that’s correct, he actually purchased a book specifically designed to improve one’s Wiffle pitch arsenal—and developed a wicked curve that Edgar couldn’t solve.

“He was always looking for an edge to win,” Edgar said.

Baseball was like oxygen for the Gonzalez brothers. When they weren’t swinging in the bedroom or the backyard cage, they were playing baseball games on Atari and Nintendo. On vacations, the family would bring bats, balls, and gloves so the boys could practice on the closest field or beach.

Even religion took a backseat to baseball. The Gonzalezes were practicing Catholics, but weekend tournaments often trumped Mass. “God will forgive us if we don’t go to church,” David Sr. told his boys, “as long as we’re playing baseball.” Dubious theology, yes, but you catch the drift.

Each brother became a star in his own right. David Jr. was good enough to spark college interest from the University of California Riverside and San Diego State. The Montreal Expos even offered to sign him as an undrafted free agent. He ended up at Point Loma Nazarene University, an NAIA program in San Diego, where he led the team in runs scored (38) as a junior in 1996, played every position during one game as a senior, and graduated with an engineering degree.

Edgar, meanwhile, starred at San Diego State before Tampa Bay drafted him in the thirtieth round in 2000. In 2011, he completed his twelfth professional season with the Fresno Grizzlies, the San Francisco Giants’ Triple-A affiliate, where he hit .315 with career highs in home runs (14) and RBIs (82). Even if he never gets back to the majors, Edgar can always say that he played alongside Adrian at Petco Park, appearing in 193 games for the Padres between the 2008 and 2009 seasons.

The best of the Gonzalez bunch, though, was the baby brother. A power-hitting first baseman, Adrian destroyed opposing pitching as a prep star, batting .559 in his final two seasons at Eastlake High School in Chula Vista. As a senior, he hit .645 with 13 home runs and earned Player of the Year honors from the California Interscholastic Federation and the San Diego Union-Tribune newspaper.

Later that year, the Florida Marlins drafted him No. 1 overall, making him the first high school infielder since Alex Rodriguez in 1993 to be the top pick. Before Adrian, the only other first baseman selected first since the draft started in 1965 was Ron Blomberg (Yankees) in 1967.

One day after being drafted—only twenty-nine days after his eighteenth birthday—Adrian signed with Florida for $3 million. He splurged on a Cadillac Escalade, but, always the sensible kid, he invested most of his remaining bonus.

Stardom seemed inevitable. But it didn’t come easily.

Destined for Greatness

Things started well enough. The Marlins quickly assigned Adrian to their Gulf Coast League rookie affiliate in Melbourne, Florida, where he hit .295 in 53 games and showed a deep hunger to improve.

At night, the Marlins’ prized bonus baby would sneak into town to take extra batting practice at a local cage, feeding quarters into the machines like an eager Little Leaguer. When manager Kevin Boles found out, he quickly put the kibosh on it. No overexertion for this future star, thank you.

“I still have my reports on him from back then,” Boles said. “I put down ‘Franchise-type first baseman. Offensive force. Multiple Gold Glove winner.'”

Call Boles prescient. In 2001, Adrian exploded, hitting .312 with 17 home runs and 103 RBIs in 127 games for the Class A Kane County Cougars in Geneva, Illinois. He won the Midwest League’s MVP honors and the Marlins’ Organizational Player of the Year award. He continued his power surge in 2002 with 17 homers and 96 RBIs at Double-A Portland (Maine). But that August, he suffered a wrist injury that required offseason surgery and sapped most of his pop the following season, when he hit just .269 with five home runs and 51 RBIs at two different minor league levels.

Worried about Adrian’s future power and desperate to make a second-half playoff push, the Marlins packaged him in a July 2003 trade to the Texas Rangers for reliever Ugueth Urbina, who eventually helped wild card Florida shock the mighty 101-win New York Yankees in the World Series that fall.

Suddenly, Adrian had become expendable trade bait—a still-valuable commodity bubble-wrapped in question marks. It was a terribly frustrating year for the twenty-one-year-old.

“There were a lot of times of doubt and wondering what was going to happen,” he said.

Ironically, as Adrian’s career suddenly entered a stage of whitewater rapids, his love life was enjoying smooth sailing. In January 2003, he married Betsy Perez, his teenage sweetheart. Adrian and Betsy had met at Bonita Vista Middle School in Chula Vista, but it certainly wasn’t love at first sight.

“At the beginning, Adrian was always trying to go out with her,” Edgar Gonzalez recalled. “She had a boyfriend and was always standoffish.”

Eventually, the Gonzalez charm won out. Adrian and Betsy became an item, even though they attended separate high schools. For Betsy’s graduation ceremony, Adrian spent some of his signing bonus on a plane that flew overhead towing the message: “I love you, Betsy…Congratulations.”

“He was pretty romantic,” Edgar said.

Early in the 2003 season, newly married and facing a professional crisis as he struggled at Triple-A Albuquerque, Adrian felt an uneasy emptiness in his heart. He had been attending Baseball Chapel services for a while, but faith in Jesus Christ hadn’t yet sprouted in his heart.

Betsy was a believer, though, and the couple’s desire to build their marriage on a strong spiritual foundation spurred Adrian. They began attending Bible studies outside the ballpark. Baseball Chapel sermons started penetrating his soul. And in April 2003, he repented and turned to Christ.

“It’s been a blessing since,” he said.

Adrian’s spiritual rebirth didn’t immediately resolve his baseball struggles. He made his major league debut with the Rangers on April 18, 2004, but with Mark Teixeira firmly entrenched at first base, Adrian shuttled back and forth between the parent club and the minors three times before Texas shipped him to his beloved Padres in a six-player deal in January 2006.

Adrian finally caught his big break later that year when Ryan Klesko, San Diego’s incumbent first baseman, suffered an early-season shoulder injury. Adrian grabbed opportunity by the throat, hitting .304 with 24 home runs and 82 RBIs in his first full regular season. The Padres made the playoffs in 2006, and Adrian’s slashing swings flummoxed St. Louis pitching at a .357 clip during a four-game National League Division Series loss. Just like that, the Padres had a hometown hero.

“Now, looking back, I’m grateful for everything that happened because it made me a stronger person and made me understand you have to leave it all up to Christ and His path for you,” Adrian explained. “If everything would’ve been gravy and you breeze right through the minor leagues and make it to the big leagues, you don’t see the need for God. It really allowed me to see that, no matter what, my focus has to be on God.”

In hindsight, the trade that sent Adrian from Texas to San Diego goes down as one of the best in Padres history. With 161 home runs, 501 RBIs, three All-Star selections, and two Gold Gloves in five seasons, he became arguably one of the three greatest position players in franchise history, alongside Hall of Famers Tony Gwynn and Dave Winfield.

Aside from his baseball prowess, Adrian was marketing gold—a well-respected Latino playing in a diverse metropolis just across the Mexican border.

“He was very popular,” longtime Padres chaplain Doug Sutherland remembered. “Being Hispanic and [the team being] close to the border, he was a great influence among the people who are Latin. Everybody had a Gonzalez jersey. He was highly thought of in the community.”

One of the greatest thrills of Gonzalez’s career was playing on the same team as Edgar. “That was a lot of fun,” Adrian said of competing with his brother. “It was a dream come true playing in San Diego.”

Inevitably, the dream had to end. Baseball economics aren’t sympathetic to small-market teams like San Diego, which often can’t afford to retain their young stars once they become eligible for free agency. So rather than watch him walk away after the 2011 season and get nothing in return, the Padres traded him to Boston for a trio of highly regarded prospects.

“You don’t make a trade like that without knowing pretty much what you’re going to get,” former Boston manager Terry Francona said. “We gave up a lot of good players for one really good player, but it is nice to see it in person. You read all the scouting reports and certainly you know about him, but when you see him every day, it’s pretty exciting.”

Welcome to Beantown, Adrian.

Fame, Fortune and the Fish Bowl

The proud, old building at 4 Yawkey Way in downtown Boston is not exactly holy ground. But for baseball nuts, it might as well be. This is where the pilgrims sojourn.

Awash in green paint and vivid memories, Fenway Park opened its doors on April 20, 1912—five days after the Titanic sank. The revered baseball shrine drips with history like a brimming bowl of clam chowdah. Here is where the Sultan of Swat—Babe Ruth—launched his first moon shots, where Lefty Grove added to his trove of pitching victories, and where the double-play combination of Joe Cronin and Bobby Doerr was magic up the middle. It’s where the Splendid Splinter—Ted Williams—hit .406 in ‘41, where Carl Yastrzemski was Triple Crowned in ‘67, and where Carlton Fisk waved it fair in ‘75.

The stories this creaky New England cathedral has generated have tiptoed between reality and mythology for generations. From Bridgeport to Bangor, young and old alike tell its tales each year at bars, on fishing piers, and in living rooms. Venerable Fenway, the oldest stadium in the majors, is the nerve center of Red Sox Nation.

And now it’s Adrian’s personal playground.

Playing in Boston is a far cry from anything Adrian was used to before. Despite his sublime stretch in San Diego, he never achieved top billing on Major League Baseball’s marquee. Not even the great Tony Gwynn, his childhood idol, could do that. A mediocre franchise history, small-market budget, near-perfect weather, and too much surf and sand all conspire to keep the Padres in baseball’s roadside motel.

Boston, meanwhile, enjoys the penthouse suite. Thanks to the New England Sports Network, a regional cable company that is partially owned by the Red Sox and reaches four million homes in the six-state New England area, the team is flush with cash. Consider: In 2011, the Padres’ payroll was a skosh below $46 million. Boston’s was $161 million.

On April 15, 2011, Adrian officially tapped into those riches, signing a massive seven-year contract extension that will pay him $21 million a year starting in 2012. That’s a lot of beans, even for Beantown.

“Remember,” Edgar told his little brother after the deal was completed, “that the money is not yours. It’s God’s. He gave it to you. It’s a bigger stage for you to glorify Him.”

“Yeah, I know,” Adrian said. His tone wasn’t haughty. It simply reflected a heart that was already prepared for such bounty.

“At the end of the day, you’re not taking any of that with you,” Adrian acknowledged. “When you pass away, God’s not going to say, Oh, that’s a great contract you acquired. He’s going to say, Because of Me, you had that contract, so what did you do with it? There’s nothing I’ve obtained or done that hasn’t been because of Christ.”

Still, all that money brings expectations by the truckload. In breezy San Diego, baseball is often an afterthought. In Boston, Red Sox fanaticism borders on clinical. This, after all, is a place that blamed eighty-six years of playoff futility on the fabled curse of a barrel-chested slugger with pipestem legs nicknamed “the Bambino.”

When Red Sox Nation pays a superstar that much coinage, it expects results. Everything about Boston’s amiable “Next Big Thing” will be scrutinized like never before. Fair or not, Adrian was expected to slay the Yankees single-handedly and ensure Boston’s third ticker-tape parade since 2004. But hey, no pressure, right?

“There is no pressure,” Adrian said straight-faced. “I’ve said all along, people talk about pressure, but who are you trying to satisfy? If you’re trying to make the writers or the front office or certain people happy, then you can put pressure on yourself. But for me, it’s being good for Christ, so my statistics don’t matter.”

Fair enough. But they matter to everyone else in Boston.

Entering the 2011 season, the city was abuzz with talk of what Adrian could do with Fenway’s cozy corners: If he posted great numbers in cavernous Petco Park, just think what he could do to the Green Monster!

Can you blame them? Adrian is a 6-foot, 2-inch, 225-pound hitting marvel who uses his lovely-as-a-Monet stroke to spray the ball to all fields.

Adrian’s new teammates got caught up in wide-eyed curiosity, too. Early in the season, they would often stop and stare at the novelty and beauty of his pregame batting-practice swings.

“He’s so fun to watch,” Red Sox catcher Jarrod Saltalamacchia exclaimed. “He’s so smooth. It’s just a beautiful swing. Number one is obviously still Griffey,” he said, referring to Ken Griffey Jr. “Griffey’s swing was the most beautiful swing ever made, but Gonzo’s is right there, man.”

Still, considering the fact that Adrian underwent right shoulder surgery in October 2010, only extreme optimists would have predicted what actually transpired in 2011. By the All-Star break, he was unquestionably the best hitter in baseball, leading the majors with a .354 batting average, 77 RBIs, 29 doubles, and 214 total bases. His 128 hits at that point were the most by any player in Red Sox history—more than Jimmie Foxx, Nomar Garciaparra, Manny Ramirez, Jim Rice, Carl Yastrzemski, and, yes, even the great Ted Williams.

“He can ruin your day really quick,” said San Francisco reliever Jeremy Affeldt, who faced Adrian when the latter played for San Diego.

While Gonzalez has always possessed power, it was his first-half batting average that induced awe. At the break, it was a whopping 70 points higher than his career average and 50 points higher than his single-season best of .304 in 2006.

You can attribute that to “smaller ballparks” like Fenway, as Adrian modestly does. Or you can say he benefitted from hitting in a lineup that featured names like Ellsbury, Ortiz, Pedroia, and Youkilis. But the fact is, Adrian is maturing as a hitter, too, and the great ones perform on the game’s biggest stages. They don’t call him A-Gone for nothing.

“He uses the whole field,” Francona said. “A lot of power hitters, like David Ortiz [Boston’s designated hitter], they’re going to take some of the field away from him. That’s okay because that’s the way [David] hits. Gonzo can manipulate the bat. You don’t see that with power hitters that much. He can loft the ball to left field. Sometimes, it looks like a right-handed hitter, which is impressive.”

The fireworks continued at the All-Star Game in Phoenix, Adrian’s fourth straight Midsummer Classic. In the Home Run Derby, he launched 30 bombs and finished second to the Yankees’ Robinson Cano. In the All-Star Game itself, his blast to right-center off Phillies star Cliff Lee accounted for the American League’s lone run in a 5-1 loss.

Adrian tailed off a bit in the second half of the season, losing the batting title in the last week of the season to Miguel Cabrera. He finished 2011 batting .338, despite being one of the few lefties in the game today who warrant a defensive shift from opposing teams. Even though the Red Sox swooned in September and lost a nine-game lead in the AL wild card race to Tampa Bay, Adrian’s long-term deal gives BoSox fans hope for another run at the Yankees.

“Everybody was just going crazy over him in Boston,” said Dennis Eckersley, the Hall of Fame closer turned Red Sox TV analyst on the New England Sports Network.

While fame and fortune have kicked down Adrian’s front door, his Christian faith has steadied him. He challenges himself by reading C.S. Lewis and fights pride by studying C.J. Mahaney’s book, Humility: True Greatness.

“He’s really unimpressed with fame,” said Doug Sutherland, the Padres’ chaplain. “He shies away from it. He doesn’t like to talk about it. If you try to talk about something, he’ll change the subject. He knows where it belongs.”

Adrian knows scripture and even injects biblical reminders into his at-bats. Every so often, he steps out of the batter’s box and eyes his bat, a 35-inch, 32.5-ounce piece of lumber from the Trinity Bat Company. It’s more than a between-pitches habit. His bat is inscribed with “PS27:1,” a reference to his favorite Bible verse,

Adrian is the antithesis of the stereotypical, modern-day superstar. He is quiet and unassuming. He looks you in the eye when speaking to you. And he’s a bit of a homebody. Nightlife isn’t his thing. He and Betsy “just like to hang out at home, hang out with our dogs, and maybe cook up a meal,” he said.

“He’s very easygoing, almost a little bit of a disarming figure,” Red Sox chaplain Bland Mason commented. “You expect to have this giant personality with his skills, but he’s pretty laid-back.”

Fishbowl, schmishbowl.

A Light in Boston

“Watch this.”

Adrian’s eyes dance with mischievousness. It’s July 2011, and Boston is in Baltimore for a three-game weekend series against its AL East foe. Game time is still three hours away, and Adrian wants to display a fun little clubhouse ritual he has.

“Jacoby!” he yells.

His teammate, All-Star center fielder Jacoby Ellsbury, doesn’t respond. He’s talking to a team public relations assistant.

Adrian tries again: “Jake!”

Ellsbury looks over.

“Say it loud and proud,” Adrian says, noisily. “Who’s the man?”

“Je-SUS!” Jacoby bellows.

Adrian grins, satisfied. He explains that Miles McPherson, his pastor at San Diego’s Rock Church, near his offseason home in La Jolla, does the same thing with the congregation during sermons.

“So I had Jacoby listen to it, and he loves it,” Adrian says. “So now he’ll yell it at me, and I’ll yell it at him.”

Baseball clubhouses aren’t exactly church choir lofts. Foul language, raunchy humor, and lewd music are often the soundtrack du jour of locker rooms. In this dark environment, Adrian winsomely shines the light of Jesus.

His teammates, by all accounts, have responded at every stop. In San Diego, he once used his bilingual abilities to encourage a Spanish-speaking teammate to attend chapel (“If Adrian hadn’t brought him, I don’t think he’d be coming,” Sutherland said), and he also helped save another teammate’s marriage by pointing him to Sutherland for counseling.

“From that, this couple became Christians and have a great walk with the Lord,” Sutherland said. “That’s the kind of influence Adrian has. He’s watching. He’ll get guys to come to chapel and get counsel and encourage them. He’s an influencer in that way. He’s not aggressive in the sense of making people uncomfortable with Christianity. With his success, people listen, but they also listen because of his character.”

After Adrian met Mason during his first Red Sox spring training in 2011, he immediately asked the Boston chaplain what his spiritual vision for the team was and offered to lead Bible studies on road trips. During the first half of the season, he led his new Christian teammates in a book study of Mahaney’s Sex, Romance, and the Glory of God. (The previous year in San Diego, he led a book study of Jerry Bridges’ The Pursuit of Holiness.)

During the 2011 season, he also helped organize Boston’s first Faith Night in at least thirty years. Adrian, Saltalamacchia, outfielder J.D. Drew, and reliever Daniel Bard all shared their testimonies with the crowd after a game.

Adrian’s presence has been “a big uplift,” Saltalamacchia said. “That’s kind of where we struggled as a team [before]. We’ve had some guys who have been in the faith, but Bible studies have been four guys or three guys. When he came in, we talked about it, and…he’s delivered every bit of it. He’s getting Bible studies on the road, he’s getting Bible studies at home, and he’s getting Faith Night in Boston. He’s different, man—he’s different than anybody else.”

“He’s done more than any other player than I’ve been around,” Mason added. “He’s earned instant credibility, and he’s just a consistent guy. He doesn’t shove Christ down people’s throats, but he wants to share with all his teammates. He’s a leader in the clubhouse, both as a player and a Christian.”

Adrian is active in the community, too. In August 2008, he launched the Adrian Betsy Gonzalez Foundation, which helps underprivileged youth. And in 2011, he donated a thousand dollars to Habitat for Humanity for every home run he hit. He has been involved with several other San Diego area charities, and he’s planning to expand his generosity into New England.

An Example to Follow

Who knows…right now, somewhere in Boston, a trio of fun-loving brothers could be playing bedroom baseball with Adrian Gonzalez trading cards. If so, here’s a tip, kids: don’t worry about bending those card corners. Just mimic this man—both his swing and his faith. He is greatly blessed by God and greatly blessing others.

“God has put me in a situation where I have a big platform to profess Christ to people, so I’ve got to take advantage,” Adrian said. “He’s given me abilities to play this game, and I’m grateful for that. I do the best I can with them, and in return, try to be the best disciple I can for Him.”